Rainbow Valley, despite its poetic name, isn’t a lush meadow or a vibrant floral display. It’s one of the most sobering and striking locations on the planet. Climbers find this area on the slopes of Mount Everest. Specifically, the valley sits in the “death zone”—the region above 8,000 meters (about 26,000 feet). Here, the lack of oxygen makes human survival extremely difficult without a supplemental breathing apparatus. The valley isn’t a traditional geographical depression. Instead, the term describes a high-altitude expanse, usually between Camp IV and the summit. This area is found on the North Ridge route in Tibet, though the term is sometimes applied to the South Col route. This notorious section sits at an altitude where temperatures are brutally cold, winds are fierce, and the body rapidly deteriorates. Knowing the true location and nature of this region helps to understand the tremendous risks climbers face. They attempt to reach the highest point on Earth here. It’s a powerful reminder of the mountain’s raw and unforgiving power, far removed from the safe confines of Base Camp. (145 words)

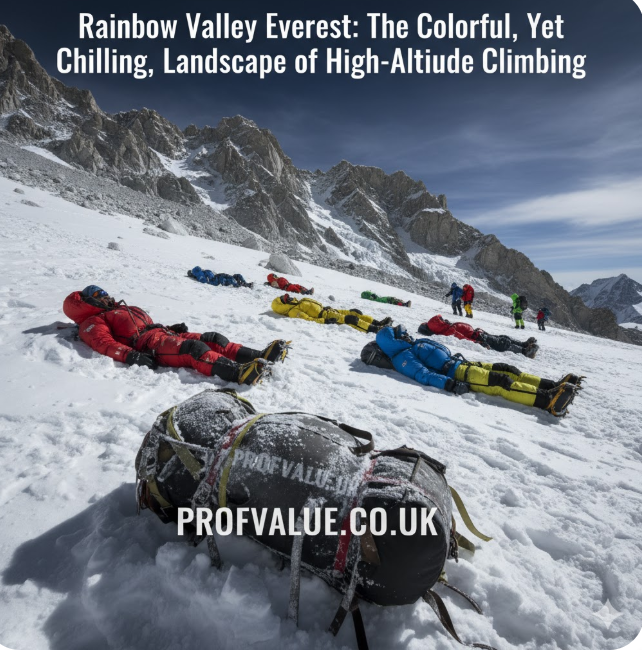

The name Rainbow Valley Everest derives from a heartbreaking phenomenon. As climbers ascend into the death zone, they often come across the bodies of those who perished on the mountain. Teams leave these bodies behind because retrieving them is too dangerous and logistically impossible. They are now a permanent, grim feature of the landscape. They remain clothed in brightly colored, high-tech climbing gear—red, blue, green, and yellow insulated suits—designed to protect against the extreme cold. These colorful suits weather the elements. They give the area its poignant and macabre name. The sight is both a stark warning and a tribute to the commitment of those who attempted the ultimate ascent. The colors are bright against the blinding white snow and grey rock. They are not a cause for celebration but a constant, silent testament to the mountain’s toll. This chilling visual is a powerful part of the Everest narrative. It forces every climber to confront the extreme dangers of this final push. (150 words)

The area encompassing the famed Rainbow Valley Everest falls firmly within the “death zone.” We typically define this as any altitude above 8,000 meters (26,247 feet). At this elevation, the air contains less than a third of the oxygen found at sea level. The human body simply cannot acclimatize or survive here for long. Every moment spent above 8,000 meters is an act of extreme endurance. The body uses up its stored energy reserves faster than it can replenish them. This lack of oxygen leads to severe health issues like High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE) and High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE). These conditions cause confusion, loss of coordination, and eventually, death. Climbers move at a painfully slow pace. They often take hours to cover what would be a few minutes’ walk at lower altitudes. The judgment of a climber can be severely impaired. This leads to critical and fatal errors. (149 words)

Mount Everest climbing has changed significantly over the decades. It was once a rare feat attempted only by highly funded, specialized expeditions. Now, it is a more accessible, though still expensive and dangerous, pursuit. Advances in gear, weather forecasting, and the increased presence of commercial guiding companies caused this shift. This rise in popularity led to an increase in the number of climbers, particularly on the South Col route. This caused “traffic jams” at high altitudes. While the North Ridge route passes directly through the most commonly referenced Rainbow Valley Everest, the South route also has its own somber landmarks. This higher volume of traffic potentially increases the risk of accidents and, sadly, the number of casualties. Some companies now offer services to clean up the mountain, focusing mainly on trash. Occasionally, they also assist in moving bodies off main paths, though complete removal remains an anomaly. To learn more about the broader impact of this commercialization, resources like profvalue offer a detailed analysis of expedition logistics and costs. (147 words)

| Zone | Altitude Range (Approx.) | Oxygen Level (vs Sea Level) | Common Challenges | Significance |

| Base Camp | 5,300m – 5,500m (17,400ft – 18,000ft) | $\sim 50\%$ – $60\%$ | Altitude Sickness, Cold, Logistics | Acclimatization Hub, Start Point |

| Below 8,000m | 6,500m – 8,000m (21,300ft – 26,200ft) | $\sim 35\%$ – $40\%$ | Falling Ice, Crevasses, HAPE/HACE Risk | The Main Ascent Path |

| Death Zone | Above 8,000m (26,200ft) | $< 33\%$ | Severe Hypoxia, Extreme Cold, Exhaustion | Summit Push, Contains Rainbow Valley |

Mount Everest can be summited from two main directions: the Southeast Ridge route (Nepal) and the Northeast Ridge route (Tibet). While the South route is historically more popular and considered less technically demanding in some sections, the North route is often characterized by extreme exposure and wind.

The North Ridge is where the specific area known as Rainbow Valley Everest is most frequently and vividly described. This route requires climbers to pass by the highest permanent camp (Camp VI) and then tackle a series of rocky obstacles, including the challenging “Three Steps.” The path here is highly exposed, and the wind chill can be deadly. The bodies left behind are often clearly visible from the main climbing line, creating the infamous sight that gives the valley its name. This exposure adds to the challenge of body recovery.

While the name Rainbow Valley is less frequently applied to the South Col route, this side of the mountain has its own grim markers, including famous bodies that serve as high-altitude signposts. The ascent from the South Col (Camp IV) is steep and grueling, culminating in the Balcony and the South Summit. The challenges of the death zone are universal on both sides, and both paths are fraught with incredible risk. Climbers on both routes share a deep understanding of the risks they are undertaking in this brutal, high-altitude landscape.

Preparation for the death zone must be all-encompassing. It’s not just about physical fitness; it involves financial, logistical, and mental readiness.

Training: Years of high-altitude and technical climbing experience are required. Climbers should be familiar with the effects of altitude before even attempting Everest.

Gear: Only the absolute best-in-class gear is acceptable—from boots and down suits to oxygen systems. Failure of a single piece of equipment can be fatal.

Team and Support: Choosing a reputable guiding company and a strong Sherpa support team is essential. Their expertise is often the difference between life and death.

Emergency Planning: Every expedition must have a clear, realistic plan for emergencies, including the decision point for turning back, which, according to the U.S. National Park Service, is a critical element of safety on any mountain climb (NPS Safety Guidelines). This decision is often the hardest and most important a climber must make.

The individuals who attempt Everest, fully aware of the grim reality of Rainbow Valley Everest, possess a unique psychological drive. For many, it is the ultimate test of human endurance, a spiritual pilgrimage, or the culmination of a life dedicated to mountaineering. They undertake the journey with a profound respect for the risks, understanding that the mountain is indifferent to their ambition. They are supported by a strong community and often draw upon established best practices in mountaineering, like those espoused by the American Alpine Club. (AAC) This mindset is critical for survival.

Q: Is Rainbow Valley a natural valley, or just a name?

A: It is a descriptive name, not a true geographical valley. It refers to the high-altitude zone where deceased climbers in colorful gear are visible on the slopes.

Q: Can you see the bodies from a helicopter?

A: While helicopters can reach very high altitudes for emergency rescues, the bodies in Rainbow Valley are often frozen into the snow and rock, making them hard to spot from a distance, and the high altitude makes sustained observation impossible.

Q: Has anyone ever successfully recovered from the death zone?

A: Yes, on rare occasions and at immense cost and risk, bodies have been recovered from the death zone, often to be moved out of the main climbing line or for burial lower down. However, it is not the norm. For most, the mountain is the final resting place.

The narrative of Rainbow Valley Everest is an indelible part of the world’s highest peak. It stands as a chilling, yet beautifully colorful, memorial to the brave souls who pushed the limits of human capability and succumbed to the mountain’s power. It is a place of profound contemplation, serving as a powerful and permanent warning about the incredible dangers that lurk above 8,000 meters. The landscape is a reminder that while the summit is a choice, the journey is an act of sheer survival. Understanding this somber reality deepens our appreciation for both the magnificence of Mount Everest and the unwavering spirit of those who dare to climb it. The best way to honor those resting there is to approach the mountain with unparalleled respect, preparation, and caution, keeping safety as the paramount concern, a principle supported by global climbing organizations such as the International Climbing and Mountaineering Federation (UIAA).

Copyright 2026 Site. All rights reserved powered by site.com

No Comments